By Edwin Rukyalekere and Michael Webber

With no end of the pandemic in sight, one can only contemplate its impact as ongoing. If history is any indication, some operational adjustments and innovations made in response to this crisis will remain long after this pandemic ends.

Business Solutions Advisor at Cirium

To better understand the impacts and the air cargo transportation industry’s responses, Edwin Rukyalekere, Solutions Engineer at Cirium, reached out to Michael Webber, a U.S.-based, international consultant specializing in air cargo planning for airport operators. The analysis leverages Cirium’s Diio-Mi Airline and Airport commercial planning analysis tool to substantiate, and in some cases, to quantify developments that have only been observed generally. Diio-Mi provides market intelligence for the aviation industry, specifically to Airline Network Planners, Revenue Managers, Corporate Sales teams and Airport Air Service Development professionals.

With global passenger traffic constrained, air cargo gained unusual importance for airport managers and passenger airlines who long treated cargo as an inconvenience. While the relative imbalance of attention and resources favoring passengers inevitably will resume, spikes in demand for e-commerce and health-related commodities reflect evolving demand that predates COVID-19 and will continue after the pandemic has subsided.

Webber Air Cargo

In the U.S., prior to the pandemic, air cargo had so fallen off the radar of some passenger airlines that airport planners were often told by airline representatives to just talk to their contracted cargo handlers because the airline wasn’t motivated to provide input about cargo for airport master plans.

Also, during the same period, most legacy carriers in the U.S. no longer operated freighters and had mainly outsourced their cargo handling to third party handlers. At most airports, except for hubs, cargo had become an increasingly passive function. Consequently, many initially lacked in-house resources for the cargo-in-cabin flights required by pandemic-related demand. The ingenuity and effort most often came from handlers who were repeatedly understaffed due to passenger-oriented cutbacks.

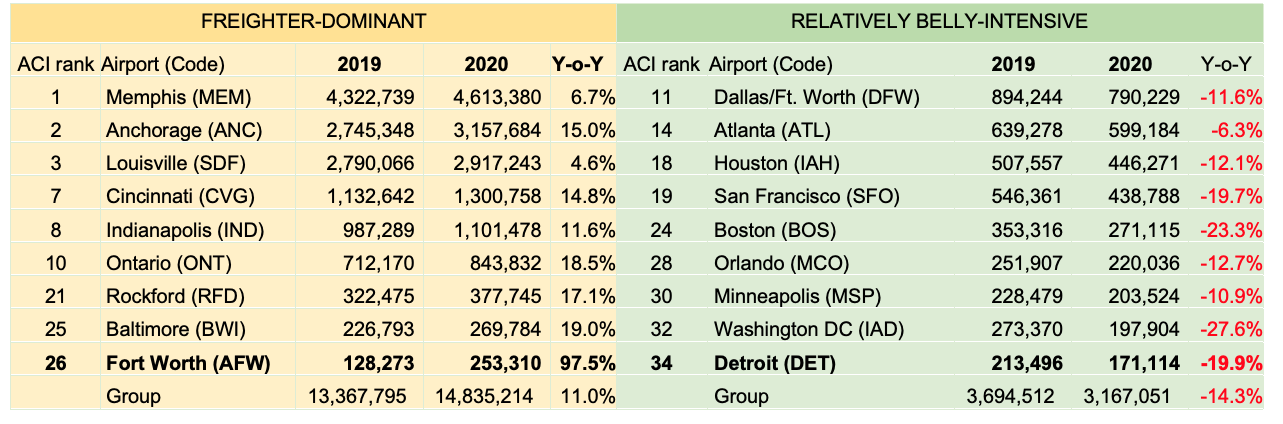

The table below shows the comparison between freight heavy airports versus the hubs that operate predominantly belly cargo aircraft. The table shows where airports that relied heavily on freighter jets increased their tonnages last year versus the year before; whereas hubs that managed mostly belly cargo carried less cargo in 2020 in comparison to 2019, given fewer belly cargo aircraft were flying during the pandemic. All in all, freight heavy airports increased their overall tonnage capacity by 11% compared to the belly cargo airports that had a total reduction of 14.3% year on year.

For illustrative purposes, we are presenting a cross-section of airports that were already freighter-intensive prior to the pandemic versus major passenger hubs more reliant upon belly capacity. Other than AFW – Alliance Ft. Worth, the tonnage data is drawn from Diio-Mi’s T-100 data module.

The airports on the left include freighter-intensive hubs for FedEx (MEM, IND, AFW), UPS (SDF, ONT, RFD), DHL (CVG) and Amazon (CVG and AFW). ANC is a transpacific freighter technical stop, as well as a sorting hub for FDX, UPS and DHL. BWI is not an integrator hub but is their preferred gateway to the Washington, DC Beltway market. None of these airports are major passenger hubs.

In contrast, the airports on the right-hand side are passenger airline hubs. Although DFW has a regional cargo hub for UPS, it was insufficient to overcome the belly capacity lost from the American Airlines hub. ATL had an extraordinary influx of charter freighters that was still insufficient to offset belly capacity lost from its Delta hub. All other passenger hubs had losses in the double digits.

The contrast between the two groups is unmistakable. Omitted are international gateways LAX, MIA, ORD and JFK that have a greater balance between freighter and belly capacity, requiring a far more granular analysis than is reasonable in this space but certainly achievable using Cirium products. Particularly interesting are metro markets with airports in each category. All-cargo AFW hosts a regional hub for FedEx, as well as a recently opened secondary hub for Amazon in the same metroplex as American Airlines’ largest passenger hub at DFW. The integrator dominated BWI shares the Beltway with international passenger gateway IAD.

To further demonstrate the effects of the pandemic in CY 2020 compared with pre-pandemic 2019, we drilled further into data at select airports. At ATL, passenger hub carrier Delta experienced a decrease of more than 40,000 Metric Tonnes in the pandemic year. Combined with smaller losses by other belly-dependent carriers, such as Virgin and British Airways, ATL’s belly cargo losses overwhelmed any gains derived from an extraordinary increase in unscheduled freighters.

Stating anything definitive in conclusion while still in the midst of a global pandemic seems unwise. The global economy was entering what would conventionally be air cargo’s annual peak period but in the most unconventional circumstances – constrained belly cargo capacity, historic disruptions in seaborne cargo and still-growing e-commerce. The commercial air cargo operators (not just airlines but their service partners in handling, trucking and forwarding) are trying to absorb and to every extent possible, accommodate capacity demand that overwhelms supply. Handlers are already being advised by airlines that cargo-in-cabin (CIC) operations are planned through at least the first quarter of 2022. The handlers and their airport landlords continue to grapple with the residual impacts on ramp operations, storage of ground service equipment and roadway congestion.

Those required to have the longer-term perspective crucial to resource planning must distinguish between the temporary demands exclusive to this unusual period and the evolutions that will outlive the ongoing pandemic and maritime crises.

Will 2023 resemble the pre-pandemic years or the pandemic-impacted 2020 and 2021? Some aspects of market share distribution will normalize when passenger networks recover enough for belly cargo capacity to meet much of its former demand. However, the need for sufficient freighter capacity to absorb the impacts of future crises has been hard-wired into customers and will not soon be forgotten. Moreover, transformational impacts such as the sustained growth of life sciences and e-commerce predate the ongoing calamities and will continue to impact demand for many more years. The future is never certain but making the most informed adjustments possible requires the most comprehensive data available, as well as the expertise to interpret what that data says about the market.

Many airlines and airports have invested much greater attention to cargo operations while the pandemic continues to restrict passenger travel. The cargo industry continues to simultaneously support and hobble global trade and investment, as one challenge after another is confronted.

As the global population continues to depend upon online shopping, cargo operations will continue to soar to new heights.

Cargo operations have been a lifeline for airlines and airports and the wider aviation industry at large as Business travel remains at a low and leisure travel picking up at a snail’s pace with some countries still enforcing lockdown rules.

In an industry that is so closely linked to local and international GDP, Cargo demand will continue to rise as shown with Cirium’s data.

Resources

Air cargo and logistics

Download the Cirium Air Cargo report

Air cargo momentum not slowing

Cabin cargo, a bright spot