READ ALL OF THE LATEST UPDATES FROM ASCEND BY CIRIUM EXPERTS WHO DELIVER POWERFUL ANALYSIS, COMMENTARIES AND PROJECTIONS TO AIRLINES, AIRCRAFT BUILD AND MAINTENANCE COMPANIES, FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS, INSURERS AND NON-BANKING FINANCIERS. MEET THE ASCEND BY CIRIUM TEAM.

By Lionel Olonga, Senior valuations analyst at Ascend by Cirium

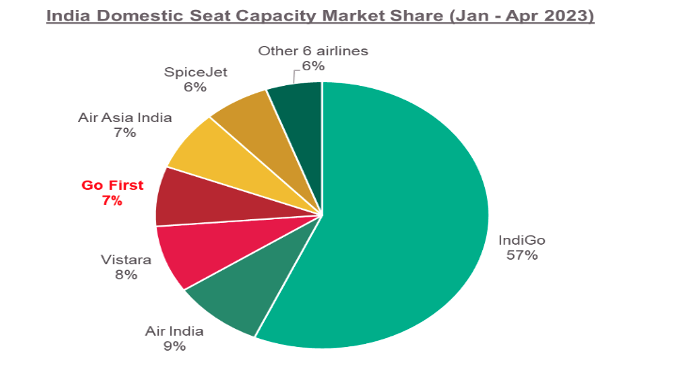

The bankruptcy of Go First has sparked renewed attention to the challenging operational environment faced by airlines in India. Being the second airline in India to declare bankruptcy within a five-year period further reinforces the challenges of an intensely competitive aviation market in the country. As the fourth largest domestic airline in India, trailing behind IndiGo and the TATA-associated airlines (Air India, Vistara), Go First’s claim that their downfall was solely a result of engine issues raises questions.

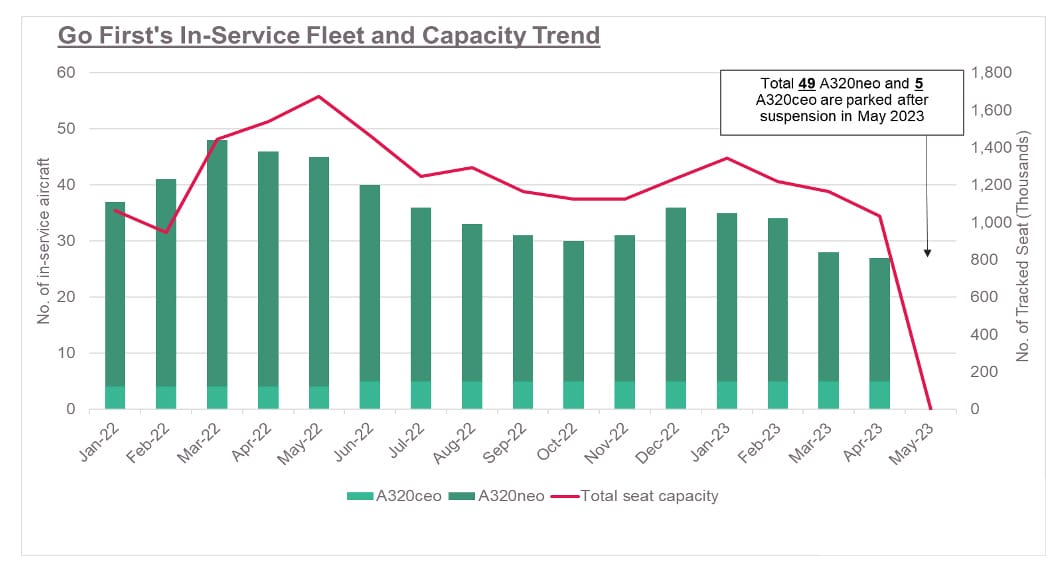

Like many other low-cost carriers (LCCs), Go First operates a single type of aircraft – a strategy similar to other prominent low-cost giants such as Southwest, Ryanair, and easyJet. By maintaining a fleet of only one aircraft type, airlines can minimise operating costs. Go First alleges that the current crisis it faces arose from engine problems attributed to Pratt & Whitney, leading to the grounding of nearly half of its Airbus A320neo fleet.

In contrast, IndiGo, which faced similar issues with the GTF engine, mitigated its risk by diversifying its engine orders, opting for the Leap 1A engines to power its future A320neo deliveries, but also more importantly having legacy IAE V2500 engines in its fleet and leasing additional A320ceo aircraft (or extending existing leases) when its A320neo orders were delayed or certain aircraft were temporarily grounded. This crucial decision enabled IndiGo to sustain its growth ambitions, even with some aircraft awaiting engines.

Another oversight by Go First was its failure to explore alternative options to maintain its capacity.

Instead of solely focusing on resolving the issues with Pratt & Whitney, they could have pursued additional capacity through wet leasing to ensure continued operations.

A notable example is the wet leases sought by Air Baltic from the market to cover its A220 fleet capacity, stemming from shop-visit delays in P&W’s aftermarket network.

The most recent developments involving Go First mean that lessors are unable to repossess a significant number of the airline’s Airbus A320 aircraft due to its voluntary insolvency plea being admitted by the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT). This bankruptcy law takes precedence in India over the Cape Town Convention, so repossession of Go First’s aircraft is now delayed for a minimum of six months. A similar case occurred recently when the Civil Aviation Authority of Vietnam de-registered aircraft, but the lessee’s shareholder filed a lawsuit, resulting in a ruling from the Hanoi People’s Court that allowed the lessee to continue managing and operating the aircraft.

Consequently, Vietnam’s compliance with the Cape Town Convention came under scrutiny, prompting revisions to the Cape Town Convention Compliance index. Note however that in this case the dispute has subsequently been resolved and the aircraft continue to fly with the airline, with agreement from the lessors.

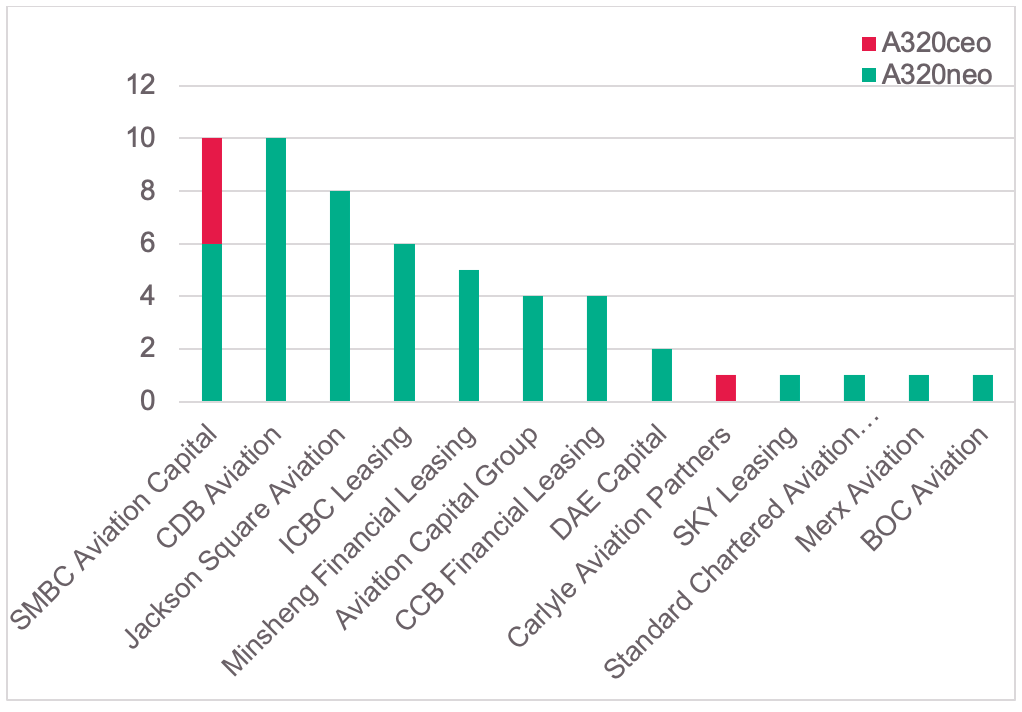

The lessors with exposure to Go First are shown in the chart below:

Several lessors, including SMBC Aviation Capital, contested a tribunal’s decision that granted Go First insolvency protection. However, an Indian appeals tribunal reaffirmed the insolvency proceedings against Go First this past Monday. Consequently, this ruling effectively halted the repossession of the aircraft.

The violation of the Cape Town Convention carries at least three potential negative consequences. First, the aircraft leasing community, already familiar with the challenges posed by Go First’s case, may adopt a stricter approach when making new lease offers to Indian carriers, and may also adjust their pricing upwards to reflect the greater perceived risk. Compliance with the Cape Town Convention is considered a prerequisite by most aircraft lessors for leasing in jurisdictions where the application of local laws is not predictable or does not guarantee access to the asset in the event of default.

Second, there is a risk of the non-compliant country being removed from the OECD list of jurisdictions with qualifying declarations, although this is not an immediate concern due to the OECD’s procedures. However, the possibility of removal cannot be ruled out.

The third risk involves the Cape Town Convention Compliance Index compiled by the Aviation Working Group (AWG), which assesses the compliance of jurisdictions with the convention. India’s score, already compromised by the Go First case, faces further jeopardy with the AWG issuing a “watchlist notice” for India.

Considering the cessation of revenue-generating services and mounting debts, the airline’s prospects for restarting operations appear increasingly unlikely over time. The temporary respite from bankruptcy protection has inadvertently fuelled the determination of the lessors to reclaim their aircraft, perceiving the airline’s actions as lacking good faith. Furthermore, even if the Wadia group were to inject much-needed capital into the airline, it is possible that a portion of the workforce has already pursued alternative employment opportunities, which make re-starting even more difficult.

Nonetheless, it is crucial not to overlook the growth potential of the Indian market. India is projected to surpass China as the world’s most populous country this year – with over 1.4 billion people, this is a market that simply cannot be ignored. Despite the challenges lessors may face, we expect that most will still want to do business in India, even if they have to adjust their risk and pricing models to continue participating.

LEARN MORE ABOUT CIRIUM FLEETS ANALYZER and Flight Schedules data – SEE MORE ASCEND BY CIRIUM POSTS.